FAQ

- Home

- FAQ

Historical Origins of the Eastern Orthodox Church

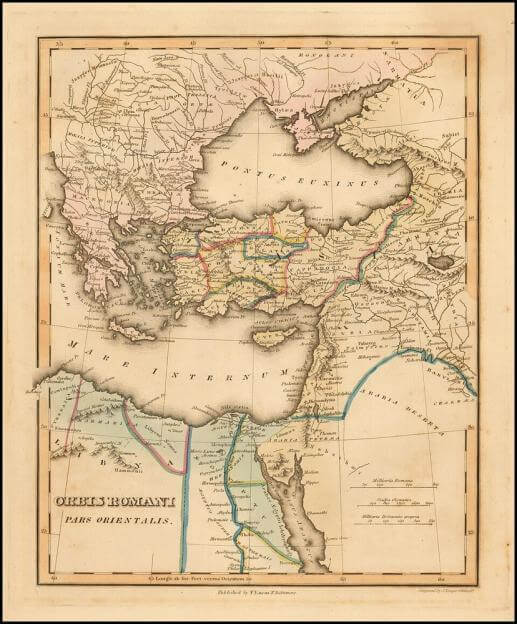

Eastern Orthodoxy traces its roots to the very beginnings of Christianity in the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Christianity first took hold in Greek-speaking lands like Syria and Egypt, with early communities forming in Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria and later in Byzantium (the city that became Constantinople) 1 . By the 4th century, Emperor Constantine I (the Great) embraced Christianity – legalizing it with the Edict of Milan (313) – and soon built a new capital at Byzantium (renamed Constantinople) . In 325 AD he convened the First Council of Nicaea (the first ecumenical council of bishops) to settle Christian doctrine

Under Constantine and his successors, Christianity became the official religion of the Eastern (Byzantine) Empire, with church councils defining key beliefs.

The Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire (map above) was the cradle of Eastern Christianity. From Jerusalem (site of Pentecost) out through Antioch and Alexandria, apostles spread the faith and established the first churches 1 . By century’s end these eastern churches coexisted alongside the old Western church in Rome, but life in the East increasingly centered on Constantinople as “New Rome.”

Key Patriarchates and Cities

- Jerusalem: The very first Christian community began here, with the apostles preaching after Christ’s resurrection. Jerusalem’s church (headed by St. James and later patriarchs) was the mother church of early Christians.

- Antioch: In Syrian Antioch one of the earliest Gentile congregations formed – it’s famously the place where followers of Jesus were first called “Christians” (Acts 11). Antioch became one of the five great patriarchates of the ancient Church , led by bishops like St. Peter and St. Ignatius in the first centuries.

- Alexandria: In Egypt, Alexandria was a famed center of learning. Its patriarchate (with leaders like Athanasius and Cyril) helped define doctrine (especially Christ’s divinity) and even gave rise to Christian monasticism. The Alexandrian church was another of the ancient sees that formed the Pentarchy of the early Church

- Constantinople: After 330 AD Constantinople was built as the new capital of the Empire. Its church grew in influence; by the late 4th century the Council of Constantinople (381) declared that “being now the New Rome,” the 2 bishop of Constantinople had authority equal to Rome 5 . In the 6th century the title “Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople” was adopted, reflecting this status. From Constantinople the Orthodox faith spread north and west: the Byzantine Empire’s religion

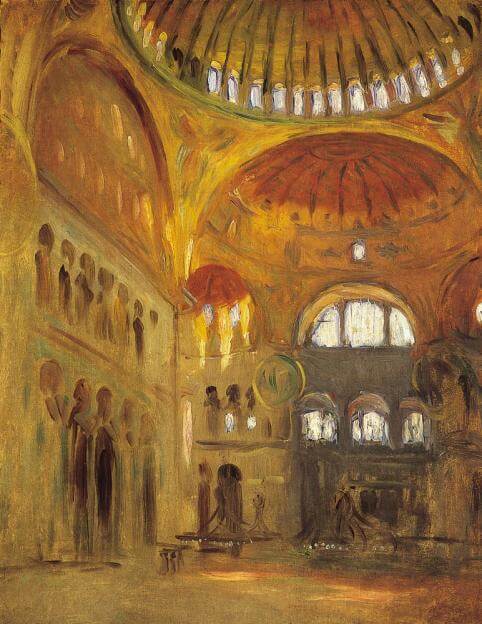

Constantinople’s great church, Hagia Sophia (built by Emperor Justinian in the 6th century), became a symbol of Eastern Orthodoxy. As New Rome’s cathedral, it embodied the union of imperial power and Christian faith in Byzantium. Under Justinian the Eastern Church also completed the codification of Roman law and reconquered parts of the old empire, reinforcing Orthodoxy’s identity with the Byzantine state 7

Distinct Church Structure and Theology

Distinct Church Structure and Theology Over time the Eastern (Orthodox) Church developed differently from the Western (Latin) Church. Instead of one single head like the Pope in Rome, the Orthodox Church organized as a family of self-governing (“autocephalous”) churches. Each major region (e.g. Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, Russia, etc.) has its own patriarch or archbishop, and they hold councils together to decide doctrine.

In Orthodox tradition the highest authority is a council of bishops (an ecumenical council), not a lone leader 8 . In fact, even by the 11th century the Patriarch of Constantinople was still officially “first among equals,” without the absolute power that later popes claimed

Theology and worship also took on Eastern characteristics. The liturgy (public worship) is usually in Greek, Church Slavonic or local languages, and it emphasizes mystery and the presence of God in the sacraments. Early Greek Church Fathers (like Athanasius, the Cappadocians, John Chrysostom and others) shaped Orthodox thought with a strong focus on the Holy Trinity and the Incarnation. By contrast the Western Church was more influenced by Latin writers like St. Augustine 9 . A famous theological difference was the Filioque controversy: in the 6th century the Western (Catholic) Church added the phrase “and the Son” (Filioque in Latin) to the Nicene Creed’s description of the Holy Spirit. The Eastern Orthodox rejected this addition, insisting the Spirit proceeds from the Father alone 10 . Small practices also differed (for example, Orthodox use leavened bread in Communion and allow married priests), but the creeds and sacraments remain the same basic faith on both sides.

The Great Schism of 1054

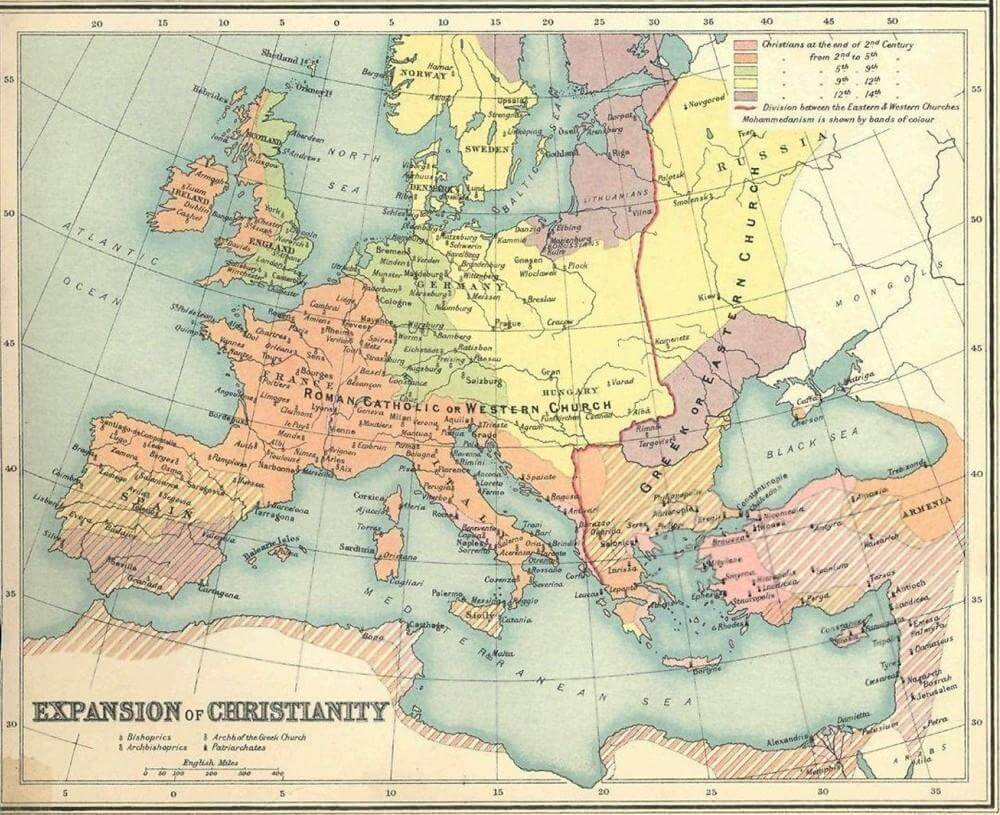

By the 11th century, long-standing differences finally led to a formal split. Tensions had been building for centuries – involving language, politics and church authority 11 – but the Great Schism is traditionally dated to 1054 AD. In that year the Patriarch of Constantinople (Michael Cerularius) and the Pope in Rome each excommunicated the other. This ended the communion between the Eastern and Western churches. From then on, the Church of Rome went its own way (eventually called Roman Catholic), while the other four ancient patriarchates (Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem) remained united as the Eastern Orthodox Church .

The split did not immediately change local faith – many rituals and beliefs were shared – but it cemented separate identities. Key issues in 1054 included papal claims of supreme jurisdiction (which the East had never accepted) 8 and disputes over the Creed (the Orthodox saw the Latin filioque as a theological error) 10 . After the Schism, each side continued without the other. The Eastern patriarchs still recognize the same seven Ecumenical Councils that had been accepted for centuries, and they refer to themselves as the “Orthodox Catholic Church” – meaning the true, universal church preserving the original faith

Today the legacy of that split is clear on a map: Eastern Orthodoxy is strong across Greece, the Balkans, Russia, Ukraine, and parts of the Middle East. By the 11th century most of the Byzantine Empire and the newly converted Slavic lands (like Kievan Rus’) were Orthodox 6 13 . This remains true: the bulk of Orthodox Christians live in Eastern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean 14 6 . Over time Orthodoxy also spread to new regions – for example, missionaries to the Balkans and Russia in the Middle Ages, and later immigrant communities around the world. Nonetheless, the church’s heartlands are still those traditional regions where it first took root.

Key figures and events: Many early leaders shaped Orthodoxy’s identity. Apostles like Andrew and Peter founded the first churches, and Fathers such as Athanasius of Alexandria (4th century) and John Chrysostom (Archbishop of Constantinople, 5th century) gave the Church its liturgies and creedal teachings. Emperor Justinian I (6th century) championed Orthodoxy and built the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. In the 9th century Saints Cyril and Methodius crafted the first Slavic alphabet to translate the Gospel,spreading the faith among Slavic peoples 15 . Major councils – Nicaea (325), Constantinople (381), Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451) and others – defined core doctrines (especially about Christ’s nature and the Trinity). The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 was another turning point: the Ottoman Empire left the Church free to govern its own affairs under 4 the Ecumenical Patriarch, even as political power waned 16 . All these people and events helped solidify the Eastern Orthodox Church’s traditions, so that today it still follows the faith and practices set in those early centuries.

Geographical spread: From its beginnings in the eastern Roman Empire, Orthodoxy spread steadily. In the Middle Ages it became the state church of countries like Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia and others . It also remained the historic faith in Greece, Anatolia and the Levant. In modern times the fall of empires and population movements have introduced Orthodoxy worldwide – but the largest communities remain where the Byzantine missionaries first preached. In short, the Eastern Orthodox Church today is the heir to the first Christian communities of the East, organized through the centuries in major sees like Constantinople and Alexandria, and defined by the councils and saints of the early Church 1 17 .

Sources: Overviews and histories of the Orthodox Church 18 11 6 , along with primary documents (council canons, church archives) and reputable church sites 10 1 were consulted to ensure accuracy. These sources trace Eastern Orthodoxy from the apostles’ time through the Byzantine era, Great Schism and beyond

Weekly Prayer Requests

Requests for the week of January 18, 2026